In Focus: The Shaping of Mexican Muse Nahui Olin

Painter. Poet. Feminist. Muse of the Mexican avant-garde. You could, of course, call her many things. But first, you’d have to trace the origin story. Born in 1893 to a wealthy Mexican diplomat, María del Carmen Mondragón, started writing poetry as a schoolgirl. Her formative years took her into the arty circles of Paris, where her father was working. She later married a Mexican diplomat Manual Rodrigeuz Lozano –who also became a famous painter. After World War I, Mondragón and Lozan returned to Mexico and enrolled at the prestigious art school Academia San Carlos. After the Revolution of 1910, Mexico was reshaping itself and Mondragón became part of the new intellectual and artistic landscape.

Museo Nacional de Arte MUNAL, Carmen Mondragón

During the early 1920s, Mondragón met the activist and landscape painter Gerardo Murillo, known primarily as Dr. Atl. In his diaries, Atl wrote about being seduced by Olin’s intelligence and intense green eyes. In literary fashion, they had a torrid affair and moved into Ex-Convento de la Merced, an old colonial-era monastery in Mexico City’s center. The couple founded an art school and Dr. Atl christened her as Nahui Olin, a Nahuatl name that translated to “the movement of the cosmos.” Olin was smitten by her rebirth: “My name is like that of all things: without beginning or end, and yet without isolating myself from wholeness by my distinct evolution in that infinite set, the closest words to name me are NAHUI-OLIN. In Aztec, the power that the sun has to move the set encompasses its system.”

Olin was also an artistic muse. In 1924, photographer Edward Weston used her as part of his Heroic Heads series. You’ll find Weston’s photograph shot at close range, as Olin looks, rather solemnly, into the camera. Olin disliked the photo, even as Weston considered it one of his best. She was also captured by French artist Jean Charlot and Mexican artist Diego Rivera (you’ll spot her sitting in gold and blue with intense-piercing green eyes in his first mural La creacion).

Credit: Self-Portrait, Nahui Olin

Feeling the creative spirit of the times, Olin worked on erotic poetry and paintings–mostly of cemeteries, pulquerias, weddings and bullfights. Her style, employing saturated colors and wide brushstrokes, also featured large exaggerated eyes. Much like Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s tumultuous marriage — Dr. Atl and Olin were also plagued by constant infidelity. Fed up, Olin finally left Dr. Atl to live alone. She spent the rest of her working life as an art teacher at a public school and continued painting, often using herself as the subject with nude (both men and women) lovers.

Still, Olin’s heartbreak took its toll. The last few decades—and much like Charles Dickens' fictional character Miss Havisham, Olin dropped out of society and spent the rest of her life in isolation with her cats in a crumbling mansion that her father left for her – and where she spent her childhood. Mostly forgotten by the art world and nearly broke, she died when she was 84. Today, her art works, and green eyes, live on.

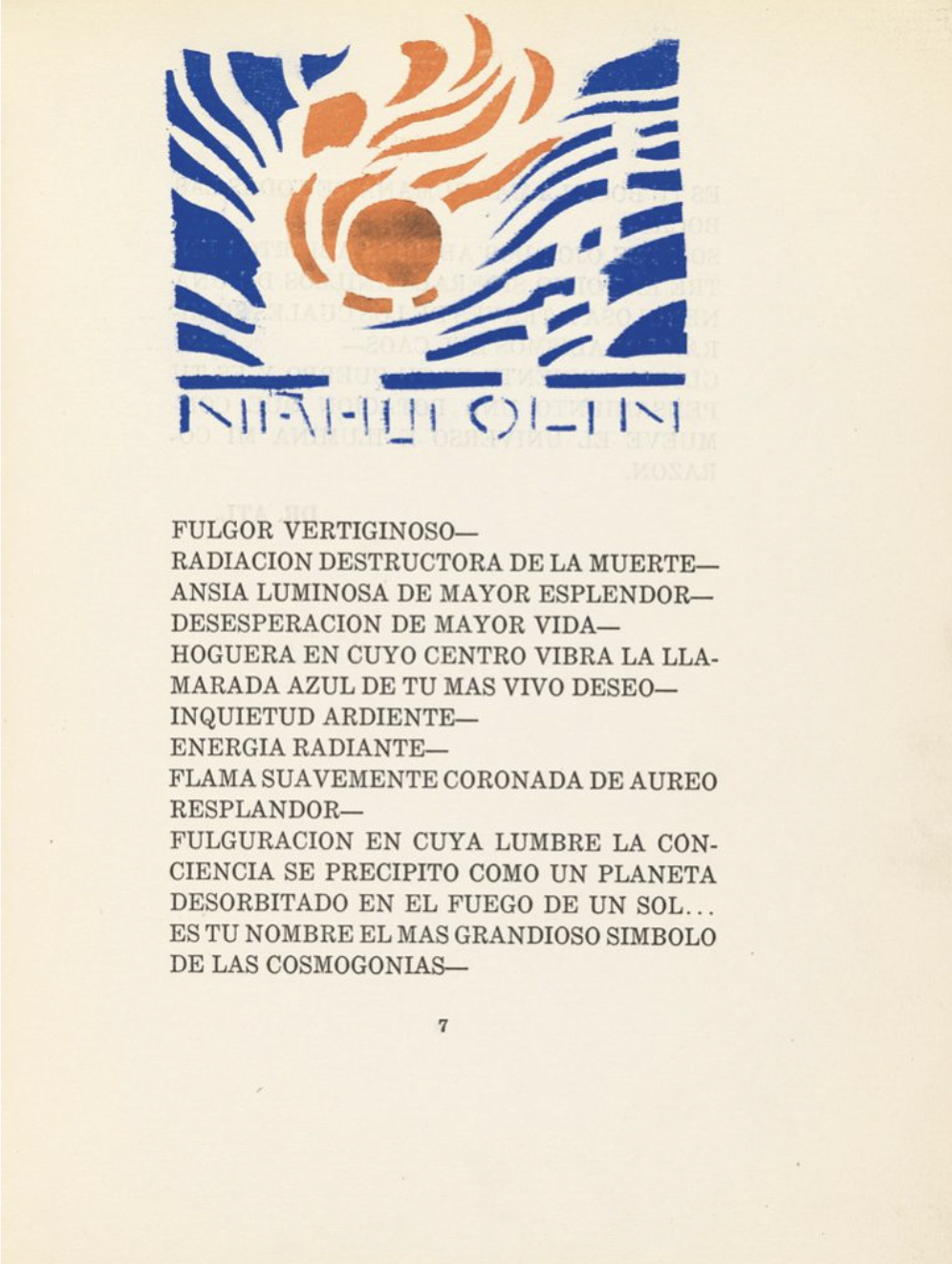

In her poem Optica Cerebral: Poemas Dinámicos (1922), we’re given a taste of Olin’s essence:

Dizzying glare –

Radiation destructive death –

Craving more luminous splendor –

Desperation for better life –

Purply blue of your greatest desire –

Burning restlessness –

Radiant energy –

Flame gently crowned gold –

Radiance –

Electrocution in whose lumber consciousness is precipitated as an extortionate planet in the fire of a sun … your name is the greatest symbol of the cosmogonies